History of Song (960–1279), Liao (907–1125), and Jin (1115–1234) Dynasties

The Northern Song Dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song in 960, following his usurpation of the throne of the Later Zhou, ending the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period. Although reunited and ably ruled for well over a century by the first five Song emperors, China failed to recover the northern provinces from the barbarian tribes. A Khitan tribe, calling their dynasty Liao, held all of northeastern China until 1125, while the Western Xia held the northwest, cutting off Chinese contact with western and Central Asia. From the new capital, Bianjing, the Song rulers pursued a pacific policy, buying off the Khitan and showing unprecedented toleration at home. While it brought Chinese scholarship, arts, and letters to a new peak of achievement, this policy left the northern frontiers unguarded.

When in 1114 the Juchen Tatars in the far northwest revolted against the Khitan, the Chinese army helped the rebels destroy their old enemy. The Juchen then turned on the Song: they invaded China, besieged the capital in 1126, and took as prisoner the emperor Qinzong, the emperor emeritus Huizong (who had recently abdicated), and the total imperial court. They then established their own dynasty, the Jin, with their capital at the city later to be called Beijing. The remnants of the Song court fled to the south in 1127 and, after several years of wandering, established their “temporary” capital at the beautiful city of Hangzhou, this is the Southern Song. The Southern Song never seriously tried to recover the north but enjoyed the beauty and prosperity of their new home, while the arts continued to flourish in an atmosphere of humanity and tolerance until the Mongols entered China in the 13th century and swept all before them. In 1234 they destroyed the Jin Dynasty, and, although the Chinese armies resisted valiantly, Hangzhou fell in 1276. Three years later a loyal Song minister drowned himself and the young emperor by jumping out of the cliff to the sea.

Culture During this Period

The Northern Song was a period of reconstruction and consolidation. Bianjing was a city of palaces, temples, and tall pagodas; Buddhism flourished, and monasteries and temples once again multiplied. The Song emperors attracted around them the greatest literary and artistic talent of the empire, and something of this high culture was carried on by their successors of Liao and Jin. The atmosphere at the Southern Song court in Hangzhou, perhaps even more refined and civilized, was clouded by the loss of the north, and the temptation to enjoy the delights of Hangzhou and neglect their armies on the frontier turned men in on themselves. Power and confidence no longer characterized Southern Song art; instead it was imbued with an exquisite sensibility and a romanticism that is sometimes poignant, given the disaster that befell China in the 13th century.

Song interest in history and a revival of the classics were matched by a new concern with the tangible remains of China’s past. This was the age of the beginning of archaeology and of the first great collectors and connoisseurs. One of the most enthusiastic of these was the Northern Song emperor Huizong, whose passion for the arts blinded him to the perils that threatened his country. Huizong’s sophisticated antiquarianism reflects an attitude that became an increasingly important factor in Chinese art. He collected and cataloged pre-Qin bronzes and jades while the palace studios turned out close replicas and archaic emulations of both media. Building his royal garden, the Genyue, was said to have nearly bankrupted the state, as gigantic garden stones hauled up by boat from the south closed down the Grand Canal for long periods. He was also the most distinguished of all imperial painting collectors, and the catalog of his collection (the Xuanhe Huapu (宣和画谱), encompassing 6,396 paintings by 231 painters) remains a valuable document for the study of early Chinese painting. (Part of the collection passed into the hands of the Jin conquerors, and the remainder was scattered at the fall of Bianjing.) Huizong also elevated to new heights the recent process of bureaucratizing court painting, with entrance examinations modeled on civil service norms, with ranks and promotions like those of scholar-officials, and with regularized instruction sometimes offered by the emperor himself as chief academician. The favors granted throughout the Song to lower-class artisans at court incurred the ire of aristocratic courtiers and provided stimulus for the rise of the amateur painting movement among these scholar-officials, which ultimately became the literati painting mode that dominated most of Yuan, Ming and Qing history.

Landscape Painting

Settled conditions and a tolerant atmosphere helped to make the Northern Song a period of great achievement in landscape painting. Li Cheng(李成), a follower of Jing Hao(荆浩) who lived a few years into the Song, was a scholar who defined the soft, billowing earthen formations of the northeastern Chinese terrain with “cloudlike” texture, interior layers of graded ink wash bounded by firmly brushed, scallop-edged contours. He is remembered especially for winter landscapes and for simple compositions in which he set a pair of tall, rugged, aging evergreens against a low, level view of desiccated landscape. As with Jing Hao and Guan Tong(关仝), probably none of his original work survives, but aspects of his style have been perpetuated in thousands of other artists’ works.

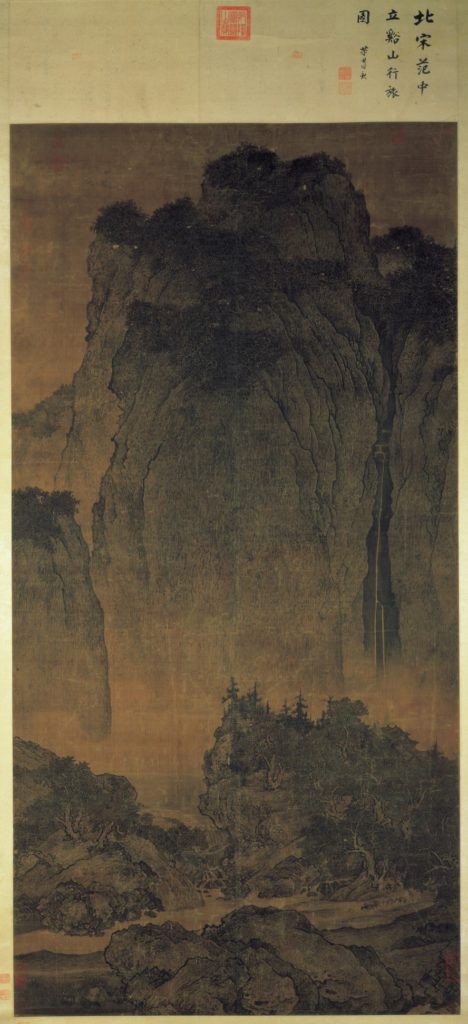

An even more formidable figure was the early 11th-century painter Fan Kuan (范宽), who began by following Li Cheng’s style but turned to studying nature directly and finally followed only his own inclinations. He lived as a recluse in the mountains of Shaanxi, and a Song writer said that “his manners and appearance were stern and old-fashioned; he had a great love of wine and was devoted to the Dao.” A tall landscape scroll, Travelers Among Mountains and Streams, bearing his hidden signature, depicts peasants and pack mules emerging from thick woodland at the foot of a towering cliff that dwarfs them to insignificance. The composition is monumental, the detail is realistic, and the brushwork, featuring a stippling style known as “raindrop” strokes, is powerful and close-textured. While the details of the work are based on closely observed geographic reality (perhaps some specific site such as Mount Heng), a profoundly idealistic conception is revealed in the highly rational structure of the painting, which conforms closely to aspects of Daoist cosmology and numerology.

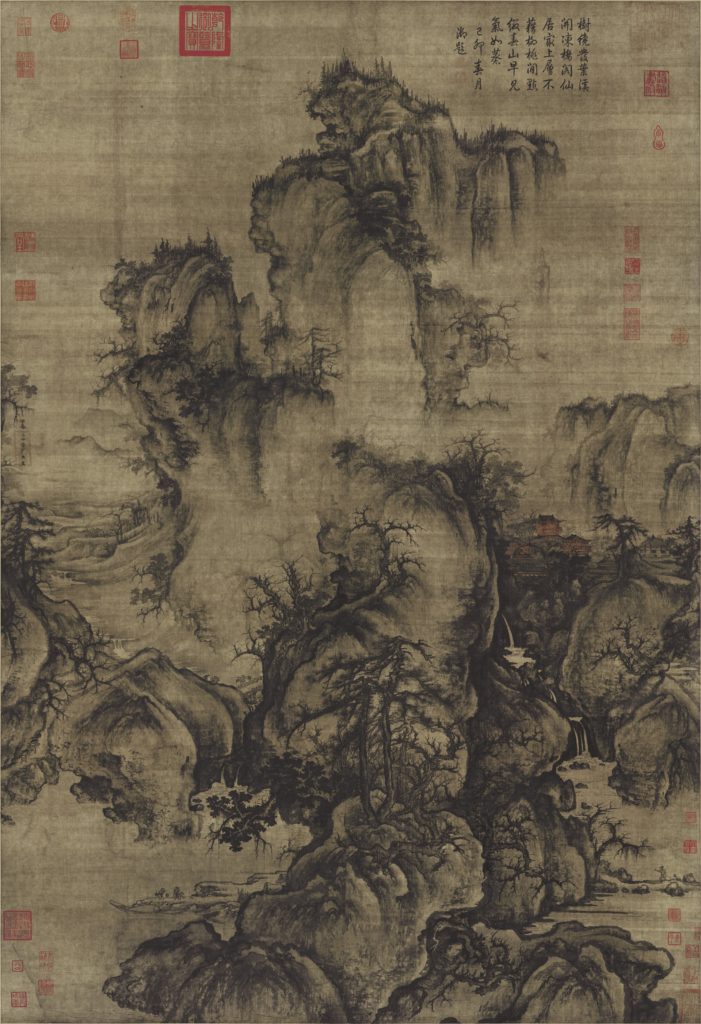

Other northern masters of the 11th century who helped to establish the great classical tradition were Xu Daoning, Gao Kegong, and Yan Wengui. The second half of the century was dominated by Guo Xi(郭熙), who became an instructor in the painting division of the Imperial Hanlin Academy. His style combined the technique of Li Cheng with the monumentality of Fan Kuan, and he made some advances, particularly in the relief that he attained by shading with ink washes (“cloudlike” texture), a spectacular example of which is his Early Spring. He was a great decorator and liked to work on such large surfaces as plaster walls and standing screens. His observations on landscape painting were collected and published by his son Guo Si under the title “Lofty Record of Forests and Streams” (《林泉高致》). In addition to giving ideas for paintings and notes on the rules of the art, in this work he stresses that the enjoyment of landscape painting can function as a substitute for wandering in the mountains, an indulgence for which the conscientious Confucian scholar-official was too busy.

Scholar, Painter, and Literati Painting

While the monumental realistic tradition was reaching its climax, quite another approach to painting was being expressed by a group of intellectuals that included the poet-statesman-artist Su Shi (Su Dongpo, 苏轼), the landscape painter Mi Fu (米芾), the bamboo painter Wen Tong, the plum painter Zhong Ren (仲仁), and the figure and horse painter Li Gonglin (李公麟). Su and Mi, together with their friend Huang Tingjian (黄庭坚), were also the foremost calligraphers of the dynasty, all three developing the tradition established by Zhang Xu (张旭), Yan Zhenqing (颜真卿), and Huaisu (怀素) in the mid-8th century. The aim of these artists was not to depict nature realistically—that could be left to the professionals—but to express themselves, to “satisfy the heart.” They spoke of merely “borrowing” the literal shapes and forms of things as a vehicle through which they could “lodge” their thoughts and feelings. In this amateur painting mode of the scholar-official, skill was suspect because it was the attribute of the professional and court painter. The scholars valued spontaneity above all, even making a virtue of awkwardness as a sign of the painter’s sincerity.

Mi Fu, an influential and demanding connoisseur, was the first major advocate and follower of Dong Yuan (董源)’s boneless style, reducing it to mere ink dots (called “Mi dots”). This new technique influenced many painters, including Mi Fu’s son Mi Youren (米友仁), who combined it with a subdued form of ink splashing. Wen Tong and Su Dongpo were both devoted to bamboo painting, an exacting art form very close in technique to calligraphy. Su Dongpo wrote poems on Wen Tong’s paintings, thus helping to establish the unity of the three arts of poetry, painting, and calligraphy that became a hallmark of the literati painting. When Su Dongpo painted landscapes, Li Gonglin sometimes executed the figures. Li was a master of plain line painting, without colour, shading, or wash. He brought a scholar’s refinement of taste to a tradition theretofore dominated by Wu Daozi (吴道子)’s dramatic style

The northern emperors were enthusiastic patrons of the arts. Huizong, perhaps the most knowledgeable of all Chinese emperors about the arts, was himself an accomplished calligrapher (he developed a unique and extremely elegant style known as “slender gold”) and a painter chiefly of birds-flowers in the realistic tradition stretching back to Huang Quan (黄铨) and developed by subsequent court artists such as Cui Bai (崔白) of the late 11th century. While meticulous in detail, his works were subjective in mood, following poetic themes that were calligraphically inscribed on the painting. A fine example of the kind of painting attributed to him is the minutely observed and carefully painted Five-Coloured Parakeet on Blossoming Apricot Tree. He demanded the same qualities in the work of his court painters and would add his cypher to pictures of which he approved. It is consequently very difficult to distinguish the work of the emperor from that of his favored court artists.

Among the distinguished academicians at Huizong’s court were Zhang Zeduan (张择端), whose extraordinarily realistic Qingming Festival scroll preserves a wealth of social and architectural information in compellingly artistic form, and Li Tang (李唐), who fled to the south in 1127 and supervised the reestablishment of the northern artistic tradition at the new court in Hangzhou. Although Guo Xi’s style remained popular in the north after the Jin occupation, Li Tang’s mature style came to dominate in the south. Li was a master in the Fan Kuan tradition, but he gradually reduced Fan’s monumentality into more refined and delicate compositions and transformed Fan’s small “raindrop” texture into a broader “ax-cut” texture stroke that subsequently remained a hallmark of most Chinese court academy landscape painting.

In the first two generations of the Southern Song, however, historical figure painting regained its earlier dominance at court. Gaozong and Xiaozong, respectively the son and grandson of the imprisoned Huizong, sought to legitimize their necessary but technically unlawful assumption of power by supporting works illustrating the ancient classics and traditional virtues. Such works, by artists including Li Tang and Ma Hezhi (马和之), often include lengthy inscriptions purportedly executed by the emperors themselves. They represent the finest survival today of the ancient court tradition of propagandistic historical narrative painting in a Confucian political mode.

Subsequently, in the late 12th and early 13th centuries, the primacy of landscape painting was reasserted. The tradition of Li Tang was turned in an increasingly romantic and dreamlike direction, however, by the great masters Ma Yuan (马远), his son Ma Lin (马麟), Xia Gui (夏圭), and Liu Songnian (刘松年), all of whom served with distinction in the painting division of the imperial Hanlin Academy. These artists used the Li Tang technique, only more freely, developing the so-called “large ax-cut” texture stroke. Their compositions are often “one-cornered,” depicting a foreground promontory with a fashionably rusticated building and a few stylish figures separated from the silhouettes of distant peaks by a vast and aesthetically poignant expanse of misty emptiness—a view these painters must have seen any summer evening as they gazed across Hangzhou’s West Lake. The Ma family’s works achieved a philosophically inspired sense of quietude, while Xia Gui’s manner was strikingly dramatic in brushwork and composition. The Ma-Xia school, as it came to be called, was greatly admired in Japan during the Muromachi and Azuchi-Momoyama periods, and its impact can still be found today in Japanese gardening traditions.

Toward the end of this period, Chan (Zen) Buddhist painting experienced a brief but remarkable florescence, stimulated by scholars abandoning the decaying political environment of the Southern Song court for the monastic life practiced in the hill temples across the lake from Hangzhou. The court painter Liang Kai (梁楷) had been awarded the highest order, the Golden Girdle, between 1201 and 1204, but he put it aside, quit the court, and became a Chan recluse. What is thought to be his earlier work has the professional skill expected of a colleague of Ma Yuan, but his later paintings became freer and more spontaneous.

The greatest of the Chan painters was Fachang (法常), who reestablished the Liutong Monastery in the western hills of Hangzhou. The wide range of subjects of his work (which included Buddhist deities, landscapes, birds and animals, and flowers and fruit) and the spontaneity of his style bear witness to the Chan philosophy that the “Buddha essence” is in all things equally and that only a spontaneous style can convey something of the sudden awareness that comes to the Chan adept in his moments of illumination. Perhaps his best-known work is his hastily sketched Six Persimmons, while a somewhat more conservative style is seen in his triptych of three hanging scrolls with Guanyin flanked by a crane and gibbons. Chinese connoisseurs disapproved of the rough brushwork and lack of literary content in Fachang’s paintings, and none appear to have survived in China. However, his work, and that of other Chan artists such as Liang Kai and Yujian, was collected and widely copied in Japan, forming the basis of the Japanese suiboku-ga (sumi-e) tradition.

Chan Buddhism borrowed greatly from Daoism, both in philosophy and in painting manner. One of the last great Song artists was Chen Rong (陈容), an official, poet, and Daoist who specialized in painting the dragon, a symbol both of the emperor and of the mysterious all-pervading force of the Dao. Chen Rong’s paintings show these fabulous creatures emerging from amid rocks and clouds. They were painted in a variety of strange techniques, including rubbing the ink on with a cloth and spattering it, perhaps by blowing ink onto the painting.